“Feel compelled to adopt a posture of self-criticism.”

Statement of Equity and Inclusion

My Outlook

As a first-generation Latinx-Mexican woman in academia, I am well acquainted with the multitude of obstacles that make the simple act of setting foot on a university campus an act of resistance and resilience. Being the first in my family to navigate higher education meant that everything was a new struggle. While I have faced many challenges on my own journey, I know that I have been afforded many privileges because of my white proximity, documentation status, ability, and cis identification. These experiences have allowed me to think and reflect on what inclusion and equity should really mean.

Inclusion and equity begins, but does not end, with recognizing differences across identities. Inclusion means our identities shouldn’t be a barrier to our progress. Equity demands each person gets what they need to reach their full capabilities. Being equitable and inclusive requires consistent acknowledgement of barriers in every facet of the classroom and well beyond. Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to explain oppression of Black women. Intersectionality as a framework, has become a useful lens by which we can understand how students bring in varying degrees of power and privilege that interlocks and intersects across identities.

Higher education should be a space where students are nourished and supported to reach their full capabilities. Amartya Sen invites us to reexamine social arrangements of inequality when he introduced the world to the capabilities approach. He defines capability as “a person’s ability to do valuable acts or reach valuable states of being; [it] represents the alternative combinations of things a person is able to do or be” (Sen 1993, 30). Students shouldn’t be regarded as an instrumental end to an economic or social structure. Instead all people should have the agency to make decisions they value to live a dignified life and reach well-being. In other words, equity requires that we recognize everyone’s needs are different. Unfortunately today, academia continues to present many barriers to students.

The work of inclusivity and equity comes to life when we adopt a model to prop up those voices that have been historically marginalized in our classroom and in our reading lists. It requires that we interrogate dominant value judgment made in the classroom and society so that we can equalize access to resources and power. When we have diverse voices at the table, we have a fuller understanding of views and needs that can inform a society that supports everyone to reach their full potential. Diversity celebrates the totality of students’ experiences and appreciates everyone’s identities.

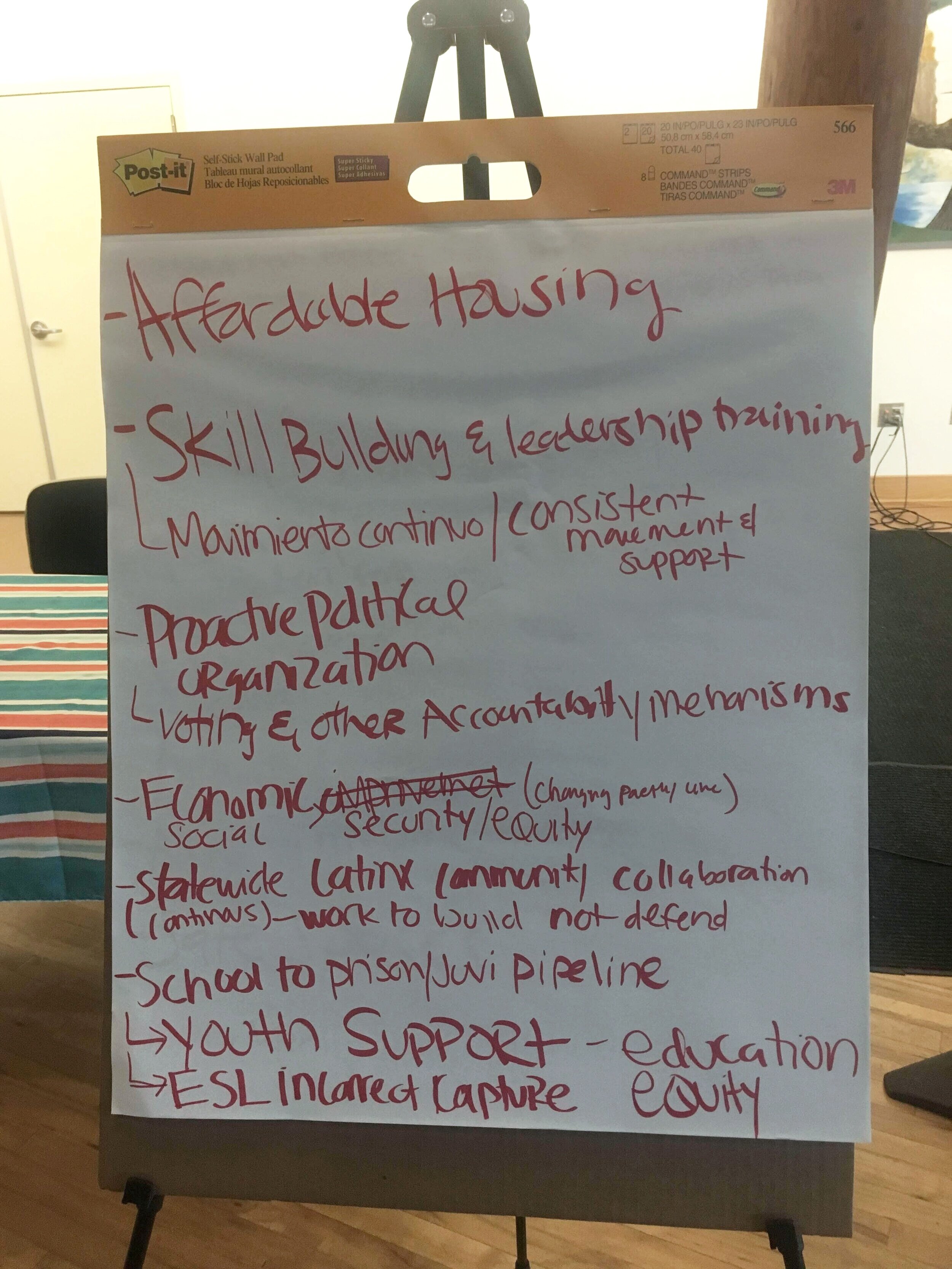

Oregon Latino Agenda for Action Biannual Summit 2018

Throughout my academic path, I can confidently say that I remained engaged in academia because of important programs like the McNair Scholars program and crucial guidance. The McNair Scholars program equipped me with the resources and tools that made me believe that I was capable of one day pursuing scientific inquiry. The program opened doors and led the way to important mentorships that I continue to benefit from and cherish today.

I take my formative experiences into the classroom. I am intentional about making myself accessible and approachable to students, just like those key mentors were to me. For example, I learn my students' names and pronouns as a way for them to feel seen. I also use extra credit as a way to bring more students into office hours and the university’s writing center. I find that this strategy motivates students that would not normally utilize these services, to do a quick check-in. Then they see these services are not so painful after all and often return again. When I see a student struggling, with grades I reach out to them and offer support. I find a simple email is often enough to push students along.

On our course site and in class, I remind students about all the resources the university provides. In each class, I make an effort to tell students about one or two opportunities occurring on campus or virtually. I also make our course site loaded with several on campus resource centers. During in class sessions I also devote ten minutes to checking-in with students. This is a moment where students can bring up any questions both related to inside and outside of the classroom. I have found that the check-in exercise optimizes class relevance and minimizes distractions, but also at times allows a healing dialogue to flourish. Overtime, I have noticed that students consistently evaluate me as accessible and willing to work with them.

Desolate: The First Ever Deported Veteran Zine

I have increasingly relied on pair-share strategies and other engagement techniques (see student assessment) to include diverse voices in the classroom, because I often notice that once predominant voices establish themselves, they are likely to be the only ones heard. I believe that during a student's academic career, we are doing much more than teaching a topic. We are also teaching students how to collaborate and relate to one another. In society, non-white voices are minimized at the highest policy levels and internalized racism can often lead to feelings of imposter syndrome. This is why I believe instructors should be vigilant of the voices allowed to dominate in the classroom, because we can be inadvertently replicating and propelling injustice.

I have also worked extensively with the university’s Disability Resource Center to make my course material accessible to all students. That includes publishing power point slides and class material well before the class session, so that students have ample time to digest the material.

As an advocate-scholar I have also devoted significant time to working at these intersections to support individuals that are often marginalized. During my time as a board member for the Oregon Latino Agenda for Action, I was able to secure funding to provide free access to our Biannual Summit event to fifty students. Students were given an important space to heal and network with other Latinx leaders and have a meaningful engagement about issues that face our communities.

I also draw on my advocacy work with deported veterans, particularly my role as Assistant Editor for Desolate, the first-ever deported veteran zine. With the zine, I can demonstrate to students the power of storytelling and its ability to change narratives and dignify people and topics that are often condemned and dehumanized. Being transparent with students about my roles outside of the classroom helps them feel more connected and empowered to also lean into their own lived experiences as a source of political resilience and advocacy.

Currently, as the membership board member of American Society for Public Administration’s Cascade Chapter, I am also contributing to our strategic planning process in a way that is intentional in diversifying our board leadership and membership. I am advocating for important student support into the art of public administration.

Black Lives Matter Protests in Portland. Blurred for anonymity and protection of protesters.

“I think that bringing people together in movements, creating solidarity [means] representing ourselves not primarily as individuals, but as members of communities of struggle.”

Stomping on Eggshells

2020 has exposed inequality ingrained throughout our systems in ways that can no longer be tolerated or ignored. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black, Indigenous and persons of color has exacerbated the consequences of injustice at the hands of a state that has failed to govern. Additionally, the justified protests that unfolded in the wake of George Floyd’s death was a reminder that we fail to protect Black life. Higher education plays a role in changing structures that protect whiteness, yet target and punish Black and Brown people simply for existing. While as a country we are reckoning with our racial past, as instructors we must be direct and upfront about how the wrongs of the past continue to live with us in the present.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Note: Data is through May 28. NY Times

In this critical time, we must strive to acknowledge how we are complicit in upholding what Charles W. Mills calls a racial social contract. We must not take racial privilege for granted and must see it as a political form of domination that is further deepened by our capitalist arrangements (Mills 2014, 1). White supremacy is defined by Frances Lee Ansley as “a political, economic and cultural system in which whites overwhelmingly control power and material resources, conscious and unconscious ideas of white superiority and entitlement are widespread, and relations of white dominance and non-white subordination are daily reenacted across a broad array of institutions and social settings (Ansley 1989, 993).”

Kyesha Jennings (2016). Overcoming Racial Tension: Using Student Voices to Create Safe Spaces in the Classroom. Faculty Focus Special Report. Magna Publication. https://provost.tufts.edu/celt/files/Diversity-and-Inclusion-Report.pdf

The classroom is an intimate space where students can either unpack these assumptions or further replicate them. It is no wonder, why our universities halls have been unsafe for our non-white and different ability student population. Therefore we must strive to make higher education and inclusive, equitable, and safe space for our increasingly diverse student population.

Change in higher education requires that we all do our part beyond empty words on diversity statements, like this one. As Angela Davis described, on the road to change “sometimes it’s important to say what you mean and have the conversations.” As I prepare to return to the classroom after the revolutionary summer of 2020, there are several strategies I am prepared to implement to help make change a reality beyond the strategies and techniques I already use (see teaching philosophy).

In the words of Keysha Jennings, it is time to stop walking on eggshells and stomp on them instead. My first method in creating change is recognizing that the youth, especially Black, Indigenous, and Brown young people have always led the way in matters of justice. I intend to incorporate ample space for students to lead the way in matters of racial justice discussion. Using students' voices can also be a method to creating safe spaces in the classroom. I draw on Jennings’s guided “Creating a Safe Space” activity to cultivate a climate where all opinions are respected and students can demonstrate the ability to think critically and connect content in broader contexts. Through a three step activity students can collectively unpack what safe and not safe means (Jennings, page 10). See graphic.

“Sometimes it’s important to say what you mean and have the conversations.”

Doing More to Speak Truth to Power

It is up to us as professors and instructors to support a cultural, social, and political change. As we begin to unlearn and relearn, we are bound to make mistakes. When these mistakes occur, it is important to teach ourselves to recognize and address our flaws. As Angela Davis described, when we “feel compelled to adopt a posture of self-criticism,” we can create change.

Academia is a setting that has been historically attainable for the most privileged social groups—with regard to class, race, gender, ability, and other intersections (Smith, Mao, Deshpande 2015). When students from these non-traditional backgrounds enter the university, they are subjected to a harsh environment riddled with intentional and unintentional microaggressions— or “the daily indignities, invalidations, and slights that are experienced by people of color (Smith, Mao, Deshpande 2015, 127).”

When instructors fail to speak up when a microaggression occurs (even if the response is not perfect), it can cause long-lasting harm to students. Cheung, Ganote, and Souza (2016) introduce us to a framework to turn microaggression into microresistance to support and empower students. They call their framework Take A.C.T.I.O.N. and it is geared to stopping or addressing microaggressions when they occur in an academic context. Through a six step process, the authors equip us with a guideline to disrupt microaggressions. Of course, we should be aware and reflective of when we as instructors are the aggressors.

Floyd Cheung, Cynthia Ganote, & Tasha Souza (2016). Microagression and microresistance: supporting and empowering students. Faculty Focus Special Report. Magna Publication. https://provost.tufts.edu/celt/files/Diversity-and-Inclusion-Report.pdf

Floyd Cheung, Cynthia Ganote, & Tasha Souza (2016). Microagression and microresistance: supporting and empowering students. Faculty Focus Special Report. Magna Publication. https://provost.tufts.edu/celt/files/Diversity-and-Inclusion-Report.pdf

Carolyn Ives (2016) gives us the important warning, that while instructors have good intentions when incorporating diversity and equity into the classroom, our efforts can indeed have the opposite effect of the goal we desire. She builds off Lopes and Thomas (2016) and provides us with a Triangle Tool to help us reposition students to locate their own social privileges. The triangle tool enables instructors to help students examine individual behaviors and underlying systemic roots (13). The top triangle point is the individual behavior, for example a racist or homophobic comment. The first bottom triangle point is where we point out the powerful statement and its accompanying unspoken belief. The bottom second point of the triangle represents the systemic forces, laws, and structures that keep the belief in place. In the center of the triangle is the impact where the students and instructors together discuss the physical and emotional abuse, pain, and suffering the comment incites. This triangle tool can be a useful way to unpack statements that are often made by students that are around a learning corner.

Carolyn Ives (2016). Classroom Tools to Defuse Student Resistance. Magna Publication. https://provost.tufts.edu/celt/files/Diversity-and-Inclusion-Report.pdf

As Rachel Cargle’s framework indicates, unlearning requires Knowledge + Empathy + Action. The classroom is an ideal place to implement this technique to continue marching down the path of unlearning and step towards equality. As instructors, we must push ourselves to do more for justice and equality. These are three tools that only skim the surface on the range of techniques available instructors should have at their disposal to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in the classroom. As an instructor, I am committed to continuing to reflect and holding myself accountable to do my part in creating an inclusive learning envious environment for all students.

Sources

Ansley, F. L. (1988). Stirring the ashes: Race class and the future of civil rights scholarship. Cornell L. Rev., 74, 993.

Mills, C. W. (2014). The Racial Contract. Cornell University Press.

Provost Tufts Edu. 2020. [online] Faculty Focus Special Report: Diversity and Inclusion in the College Classroom. Magna Publication. Available at: <https://provost.tufts.edu/celt/files/Diversity-and-Inclusion-Report.pdf> [Accessed 27 July 2020].

Sen, A. (1993). Capability and well-being73. The quality of life, 30, 270-293.

Smith, L., Mao, S., & Deshpande, A. (2016). “Talking across worlds”: Classist microaggressions and higher education. Journal of Poverty, 20(2), 127-151.

The Great Unlearn https://rachel-cargle.com/